My husband had a very specific vision for our daughter’s nursery. When it came to wallpaper, he sent me images of rose-quartz clouds, illustrations of peonies in shades of icing sugar and apple blossoms. In the furniture store, he smiled at frothing canopies scattered with seed pearls. He wanted Versailles style mirrors, a suede rocking horse, a pale changing table with crystal knobs, a roost of golden butterflies delicately holding a shelf of crinkle books and velvet toys aloft.

Of his original vision, only the golden butterflies remain.

When our daughter was in utero, I nicknamed her The Kraken. The name stuck after an ultrasound tech tried to get a photo of her face. All she caught was a demonic rictus grin which we, besotted fools, immediately displayed on our fridge to the gentle bewilderment of our relations. Kraken has always been a wriggly thing with a nefarious sense of humor. The first time she kicked I was watching Twilight: Breaking Dawn Part I where the still-mortal Bella endures a labor so grueling it snaps her spine. Bella and I shrieked at the same time.

For the most part, my husband and I agree that the final nursery décor suits the Kraken perfectly. On her wall, a mirror like the round window of a submarine whispers of another world behind the silver. Behind her crib, a dreamy whale swims in a night sky crowded with ships. Her chandelier looks like a tangle of constellations. Her changing table is a steampunk monstrosity. The only thing we disagreed on, the only thing I was adamant about keeping, was Rudy.

Rudy looks like a stag, but a stag whose flesh has been flensed and whose skull was then dipped in molten silver. His antlers are nubbed and nightmarish, and even hanging the little newborn hats from their points does nothing to soften them. For years, Rudy loomed over my writing desk and watched me complete several stories. Rudy is all that is left of the room that was once my office and is now the Kraken’s domain.

“What if it scares her?” my husband asked. “What if she’s afraid when she goes to bed?”

“Nonsense!” I countered. “Who wouldn’t be soothed to sleep beneath the baleful gaze of a demon reindeer?”

My husband does not find this amusing, but I am not overly concerned. Lest you mistake me for someone fearless, you should know that I am a gleeful coward deeply aware that I defied natural selection. As a child, I lived in fear of my parents’ unfinished basement and still tend to jump into bed so that whatever might be lurking beneath can’t grab my ankle. My fears — of the dark, of the unknown — are abstract, whereas the grotesque and specific never concerned me. Judging by the tales I was fed at a young age, it never concerned my parents or grandmothers either.

In elementary school, I delighted in sharing “the real” versions of stories. To fit into a glass slipper, Cinderella’s stepsisters cut off their heels and toes until blood filled the shoes and the prince was thus warned against his false brides. I told my classmates that the Little Mermaid died of despair and turned to sea foam. And, by the way, Zeus was, like, awful.

And those were just the Western tales.

When a teacher asked us to share our favorite stories, I volunteered the bedtime tale joyously shared by my grandmother which I will now relay to you with as much brevity as a strict word count can manage.

Once, there was a king who extracted a boon from the gods that he would never die. Denied immortality outright, he laid conditions instead: “I wish that neither man nor beast may kill me! I wish that I will not be killed during day or night! And neither inside nor outside and not by any weapon!” He then proceeded to wreak havoc on the heavens until Lord Vishnu delivered the universe from the king’s cosmic dictatorship.

Vishnu appeared to the king as neither man nor beast, but both… as a being with the head of a lion and the body of a man. He appeared neither at day or at night, but both…during twilight. He appeared neither indoors nor outdoors, but both… in the pillar of a courtyard. And when he seized the king, he used no weapon, but simply his sharp, sharp talons to disembowel him on the spot.

WELL, GOODNIGHT!

I spent many nights enthralled by those stories, torn between fear and fascination which sharpened into observation and obsession. Why didn’t the gods just send in a woman? Wouldn’t that have skirted past demon dictator’s conditions? Why do bad people get wishes granted and why aren’t there more attorneys in fairytales?

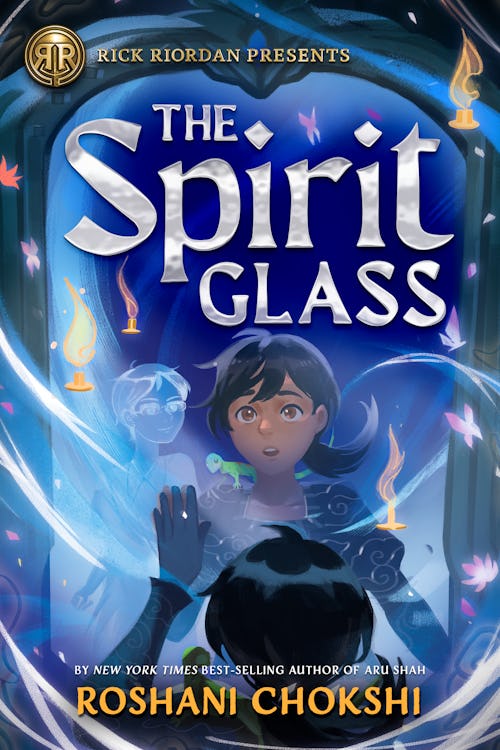

Fear provides an invaluable opportunity for exploration. Sometimes, it is an unlikely avenue for humor. Lately, I’ve been thinking of how a monster under the bed might feel neglected if the child’s room is too clean and it has no forgotten homework to munch on. Other times, fear is a window into history. Until I began researching my most recent novel, The Spirit Glass, I had not considered how the persistence of ghost stories from the Philippines rather than tales of its gods and goddesses represented the lasting scars of Spanish imperialism. Fear is a window to the sacred as well. The demon king of the tale was once a pious attendant of Lord Vishnu who agreed to become his greatest enemy because of a curse. When my grandparents immigrated from the Philippines and India, beliefs were both the heaviest and lightest belongings they carried. In this way, fear becomes a most precious heirloom.

When I held my daughter for the first time, the fear I felt was depthless and ancient. It grabbed me by my throat and flashed its endless smile: If you are fortunate, you shall know me, always. That fear stole into my bones and made me a parent.

I do not want my daughter to be fearless. I want her to know a thousand fears and recognize the familiar scaffolding upon which they hang. I want her to take fear and make it humorous. I want her to hold fear up to the light and recognize it as a piece of the hallowed or a piece of history. I want her to sew the ragged edges of fear into a story she can repeat to herself until she can fold it into something that can fit comfortably into her palm.

Fear has purpose. One of my favorite smudged quotes — so smudged by a litany of authors that I have selected one that best celebrates the spirit of the statement despite ignoring its specifics — is this: “Fairy tales are more than true — not because they tell us dragons exist, but because they tell us dragons can be beaten.” (Neil Gaiman’s smudge of G.K. Chesteron’s writing from the 1909 Tremendous Trifles).

When my Kraken is old enough, I will tell her that Rudy is not a demon reindeer. I will tell her that he is a reformed nightmare, chastened by his antics and determined to set things right, starting with being her guardian of dreams. But there will be moments where neither I nor her father will be there to wrestle her fear into a framework or a fable. It is then that I hope these heirlooms of horror will come in handy. Look close, my love, in one light the stories are a wonder; but in another, they are a weapon. After all, what better arsenal exists than the endless fire of your imagination?

Roshani Chokshi is the New York Times best-selling author of the Pandava quintet with more than 750K copies sold. Her first book, ARU SHAH AND THE END OF TIME, launched the Rick Riordan Presents imprint and was named one of the 100 Best Fantasy Books of All Time by Time magazine. In her new middle grade book, THE SPIRIT GLASS (Disney) Roshani Chokshi pays tribute to her Filipino heritage in a story that has all the magic, sparkle, and heart that made her Aru Shah series a fantasy classic. www.roshanichokshi.com.

0 Comments